Introduction

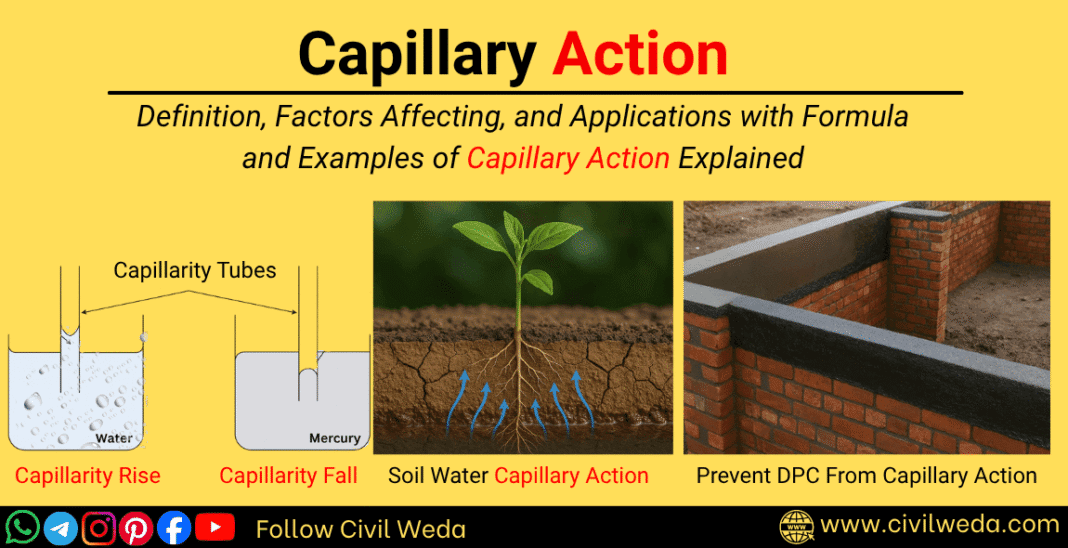

Have you ever noticed damp patches slowly appearing on the walls of a building, or wondered how plants manage to draw water from the soil without any pump? Both of these everyday observations are results of a fascinating natural phenomenon known as capillary action.

In simple terms, capillary action is the ability of a liquid to rise (or sometimes fall) in a narrow space such as a thin tube or the tiny pores found in materials like soil, bricks, and concrete. This happens due to the combined effects of adhesion, cohesion, and surface tension of the liquid.

In civil engineering, understanding capillary action is extremely important because it directly affects how water moves through soil and construction materials. This movement can lead to issues like dampness in walls, efflorescence, and even structural damage if not controlled properly.

In this article, we’ll explore the science behind capillary action, its mathematical expression, and most importantly, its applications and effects in civil engineering, from water movement in soil to moisture rise in building materials. Let’s get started:

What is Capillary Action?

Capillary action is the phenomenon by which a liquid rises or falls in a narrow tube or within the fine pores of a material due to the combined effects of adhesive, cohesive, and surface tension forces.

Let’s understand it in simple terms:

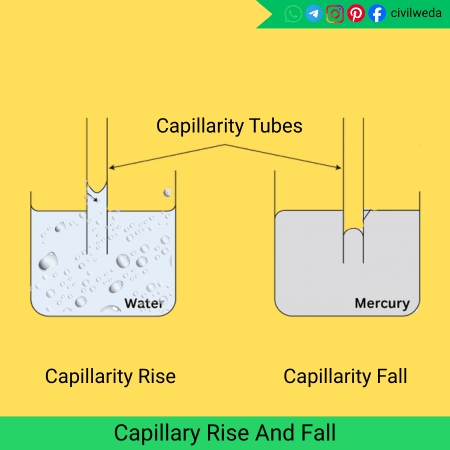

When one end of a thin glass tube, called a capillarity tube, is dipped in water, the water level inside the tube rises above the surrounding water level. This happens because water molecules are attracted to the glass surface (adhesion) more strongly than they are to each other (cohesion). As a result, the liquid climbs upward; this upward movement is called capillary rise.

If we repeat the same experiment with mercury, the opposite happens — the mercury level inside the tube falls below the outside level. This is called capillary depression, and it occurs because the cohesive force between mercury molecules is stronger than its adhesion to glass.

Hence,

- If adhesion > cohesion → capillarity rise (example: water in glass)

- If cohesion > adhesion → capillarity fall (example: mercury in glass)

In real-world materials like soil, bricks, and concrete, millions of tiny capillary pores act just like these thin tubes, allowing water to move upward against gravity, a major cause of moisture and dampness in structures.

I hope you understand capillary action. Now, let’s understand the Formula…

Capillary Rise Formula

The height up to which a liquid rises or falls in a narrow tube or in the tiny pores of a material is given by a relation called the capillary rise formula.

Where,

- h is the height of the capillary rise and fall

- T is the surface tension of the liquid,

- θ is the angle of contact between the liquid and the solid surface,

- r is the radius of the tube or pore,

- ρ is the density of the liquid, and

- g is the acceleration due to gravity.

Note: This formula is also used for capillary fall, in which a negative sign is used.

With this formula, we can clearly understand how different factors control the height of capillary rise and fall.

The height of rise (h) is inversely proportional to the radius (r) of the tube or pore. So we can say, the smaller the tube or pore size, the higher the rise of liquid. That’s why fine-grained soils like clay or silt show more capillary rise compared to coarse sand, because they have much smaller pores.

The rise also depends on the surface tension (T) of the liquid. Liquids with higher surface tension, such as water, can rise higher than liquids with lower surface tension, like alcohol.

Another important factor is the contact angle (θ), which decides whether the liquid will rise or fall.

- If θ < 90°, the liquid wets the surface, leading to capillary rise (as seen with water in a glass).

- If θ > 90°, the liquid does not wet the surface, resulting in capillary fall (as seen with mercury in glass).

In the case of capillary fall, the cohesive force between the liquid molecules is stronger than their adhesion to the surface.

As a result, the liquid surface curves downward (concave down) and the liquid level inside the tube becomes lower than the outside level, just like mercury in a glass tube.

For example, if a very thin glass tube of radius 0.5 mm is dipped into water, the water will rise about 3 cm inside the tube. This clearly shows how powerful capillary forces can be, even though they act on a very small scale; their effects in soils, bricks, and concrete are significant for civil engineers to understand.

Capillary Action in Nature (Plants & Soil)

Capillary action is not just a laboratory phenomenon; it is continuously happening all around us in nature. One of the best natural examples is how plants absorb water from the soil without a pump.

Inside plants, there are thousands of thin tubes called xylem vessels. These vessels act just like capillary tubes. When the roots of a plant are in contact with moist soil, the water molecules get attracted to the walls of these tiny tubes (adhesion), and other water molecules follow them upward (cohesion).

As a result, water moves upward through the stem and finally reaches the leaves, helping the plant transport essential nutrients along with water.

A similar process happens in soil. Soil contains numerous small pores and voids that act like tiny capillary tubes. Water from the lower layers moves upward through these pores due to capillary forces, especially in fine-grained soils such as clay and silt. This upward movement of water helps to keep the upper soil layer moist even when there is no rainfall for several days.

However, the same phenomenon that benefits plants can also cause problems in civil engineering. The rise of water in soil may lead to the upward movement of moisture into the foundations of buildings, which is one of the main causes of dampness in walls.

So, whether it is plants absorbing water, soil retaining moisture, or structures facing dampness, the same natural process, capillarity action, is at work everywhere.

Capillary Action in Civil Engineering

In civil engineering, capillary action plays an important role in understanding how water moves through building materials and soils. Materials such as bricks, concrete, and mortar contain a large number of tiny pores that act like small capillary tubes. When these materials come in contact with moisture or groundwater, water starts rising through these pores due to capillary forces.

This upward movement of water is useful in natural soils, but in construction materials, it often leads to serious problems like dampness, efflorescence, and even a reduction in the strength of structures. You might have seen old buildings where the lower portion of the walls looks darker or wet. This happens because of capillary rise in bricks or plaster.

In foundations, if the ground is moist and no proper damp proofing is provided, water can rise several centimetres above the ground level. Over time, this can cause peeling of plaster, salt deposits, corrosion of reinforcement, and even fungal growth on walls.

To prevent such damage, engineers use a Damp Proof Course (DPC), which is a horizontal layer of waterproof material (like bitumen coating or plastic membrane) provided between the foundation and the wall to stop the upward movement of water.

Capillary action is also considered while studying soil behaviour in geotechnical engineering. The height of capillary rise helps engineers decide the safe depth of foundations and the type of drainage or waterproofing system needed to protect structures.

In short, capillary action is not just a theoretical concept. It directly affects the durability, safety, and service life of structures. Understanding and controlling it is an essential part of good engineering practice.

Factors Affecting Capillary Rise

The height of capillary rise does not remain the same in every condition. It depends on several physical properties of the liquid, the material, and the environment.

Let’s look at the main factors that affect capillary rise.

1. Radius of the Tube or Pore

The smaller the radius of the tube or the pore, the higher the capillary rise.

In fine-grained soils like clay and silt, the pores are very small, so water can rise to a greater height.

In coarse-grained soils like sand or gravel, the pores are large, so capillary rise is very small.

That’s why engineers always consider the soil type while designing foundations and flooring systems.

2. Surface Tension of the Liquid

Liquids having higher surface tension show more capillary rise.

For example, water has higher surface tension than alcohol, so it rises higher in the same capillary tube.

Surface tension depends on the type of liquid and its temperature.

3. Contact Angle (θ)

The angle between the liquid surface and the solid surface, known as the contact angle, decides whether the liquid will rise or fall.

If the contact angle is less than 90°, the liquid wets the surface and rises (like water in a glass). If the contact angle is greater than 90°, the liquid does not wet the surface and falls (like mercury in glass).

4. Temperature

An increase in temperature decreases the surface tension of a liquid, which reduces the height of capillarity rise.

This means capillary action is slightly weaker in hot conditions compared to cooler ones.

5. Type and Nature of Material

Porous and fine-textured materials like brick, concrete, or clay show greater capillary rise because of their small pores.

Dense materials with fewer pores, such as granite or metal, show almost no capillary rise.

6. Density of the Liquid

Liquids with higher density show a lower rise because heavier liquids require more force to move upward. That’s why mercury (which is dense) shows capillary fall instead of rise.

👉 Note: All these factors also affect capillary fall in the same way — but in that case, the cohesive force of the liquid is stronger than its adhesion to the surface, so the liquid level moves downward instead of upward.

Effects and Engineering Problems Due to Capillary Action

Capillary action is a natural process, but in civil engineering, it often creates unwanted effects in soils and building materials. When water rises through the fine pores of bricks, concrete, or soil, it carries dissolved salts and moisture upward. Over time, this leads to several visible and hidden problems in structures.

Let’s understand some common effects

1. Dampness in Walls and Floors

The most common problem caused by capillary rise is dampness. Water rising from the ground enters brickwork or plaster and makes the walls wet and dark. This not only spoils the appearance but also reduces the life of plaster, paint, and finishes.

2. Efflorescence

As the water carrying salts evaporates from the surface, it leaves behind white salt deposits. This phenomenon is called efflorescence. You must have seen white patches on old brick walls; that’s the result of continuous capillary action followed by evaporation.

3. Reduction in Strength of Materials

Moisture weakens the bond between cement and sand in plaster or mortar. Continuous dampness also reduces the compressive strength of bricks and concrete, making them less durable over time.

4. Corrosion of Reinforcement

In reinforced concrete structures, moisture rising through pores can reach the steel bars. This causes corrosion, leading to cracks, spalling, and loss of strength in structural members like beams, slabs, and columns.

5. Peeling of Paint and Plaster

When moisture keeps entering walls, the paint starts bubbling and peeling off. Plaster also loses adhesion and begins to crack or flake away. This not only looks bad but also exposes the wall to more moisture, creating a continuous damage cycle.

6. Unhygienic and Damp Conditions

Damp walls promote the growth of fungus, mould, and bacteria, which can cause allergies and breathing problems. Hence, controlling capillary rise is important not just for structural safety but also for healthy living conditions.

In short, capillary action may look harmless at first, but if ignored, it can silently damage a structure from the inside. That’s why engineers always focus on controlling or preventing capillary rise through proper design, material selection, and waterproofing techniques.

Prevention and Control Measures of Capillary Action

In civil engineering, completely stopping capillary action is almost impossible, but it can be controlled and minimised through proper design and construction practices. By reducing the movement of moisture through pores, engineers can protect structures from dampness and related damage.

Here are some effective methods used to prevent the harmful effects of capillary rise 👇

1. Providing Damp Proof Course (DPC)

A Damp Proof Course is the most common and effective method to stop water from rising through walls. It is a horizontal layer of waterproof material such as bitumen, plastic membrane, or cement mortar mixed with waterproofing compound provided between the foundation and the wall. This layer acts as a barrier and prevents moisture from moving upward by capillary action.

2. Use of Waterproofing Compounds

Adding waterproofing admixtures to concrete or mortar reduces their porosity and water absorption. Compounds such as calcium stearate, silicates, and bituminous emulsions are commonly used to make construction materials more water-resistant.

3. Use of Dense and Low-Porosity Materials

Dense materials have fewer and smaller pores, which restrict capillary movement. Using well-compacted concrete, quality bricks, and properly cured mortar can significantly reduce capillary rise. Avoid using under-burnt or porous bricks in walls exposed to moisture.

4. Surface Treatments

Applying a water-repellent coating, such as paint, plaster, or cement-based coating, on the external surfaces can prevent moisture from entering. For example, silicone-based paints or bituminous coatings are effective barriers against capillarity action in walls and roofs.

5. Proper Site Drainage

Good drainage around the building prevents the accumulation of water near foundations. By lowering the water table and keeping the surrounding soil dry, the chances of capillarity rise are drastically reduced.

6. Providing Air Gaps and Ventilation

In some cases, air gaps or cavity walls are provided in buildings to separate the damp surface from the inner wall. Proper ventilation also helps evaporate any moisture that rises, maintaining a healthy environment inside the structure.

7. Maintenance and Regular Inspection

Regular inspection of walls, joints, and floors helps identify early signs of dampness. Timely maintenance, such as repairing cracks or renewing waterproof coatings, prevents the spread of moisture through capillary action.

In conclusion, capillarity rise is a natural process that cannot be fully eliminated, but with proper construction practices, quality materials, and effective waterproofing, its effects can be minimised. Preventing moisture at the foundation level ensures a stronger, safer, and longer-lasting structure.

Read more Civil Engg Topics

- Viscosity

- Portland Cement

- Bitumen Waterproofing

- Instruments used in a chain survey

- Bulking of sand

- Bitumen concrete

- Geopolymer Concrete

- Pile Foundation

- Vapour Pressure

- Ready Mixed Concrete

Conclusion

Capillarity action may seem like a small and invisible process, but its impact on both nature and engineering is significant. It is the same force that helps plants absorb water from the soil and, at the same time, causes dampness and damage in buildings when ignored.

For civil engineers, understanding this simple phenomenon is essential. It helps in designing better foundations, waterproofing systems, and durable structures. By controlling capillarity rise through proper materials, damp proofing, and good construction practices, we can prevent long-term structural problems and maintain the strength and beauty of our buildings.

1. Why does capillary rise occur?

It occurs because the adhesive force between the liquid and the solid is stronger than the cohesive force between the liquid molecules.

2. Why is capillary action important in civil engineering?

It helps engineers understand moisture movement in soils and building materials to design durable, waterproof structures.

3. Which type of soil shows maximum capillary rise?

Fine-grained soils like clay and silt show maximum capillary rise due to their small pore size.

Thank You for Reading! 🙏

We hope this article helped you clearly understand capillary Action in civil engineering. If you found this complete article useful, please share it with your friends and university students. For more informative posts on civil engineering topics, stay connected with Civil Weda. 🚀